The Water Act does not contain specific standards for microplastics. Studies show that synthetic sports pitches can release plastic fibres which, as they wear down, enter watercourses, the air, or the soil and may eventually reach groundwater. Methods for measuring microplastics vary considerably, which explains why results differ widely.

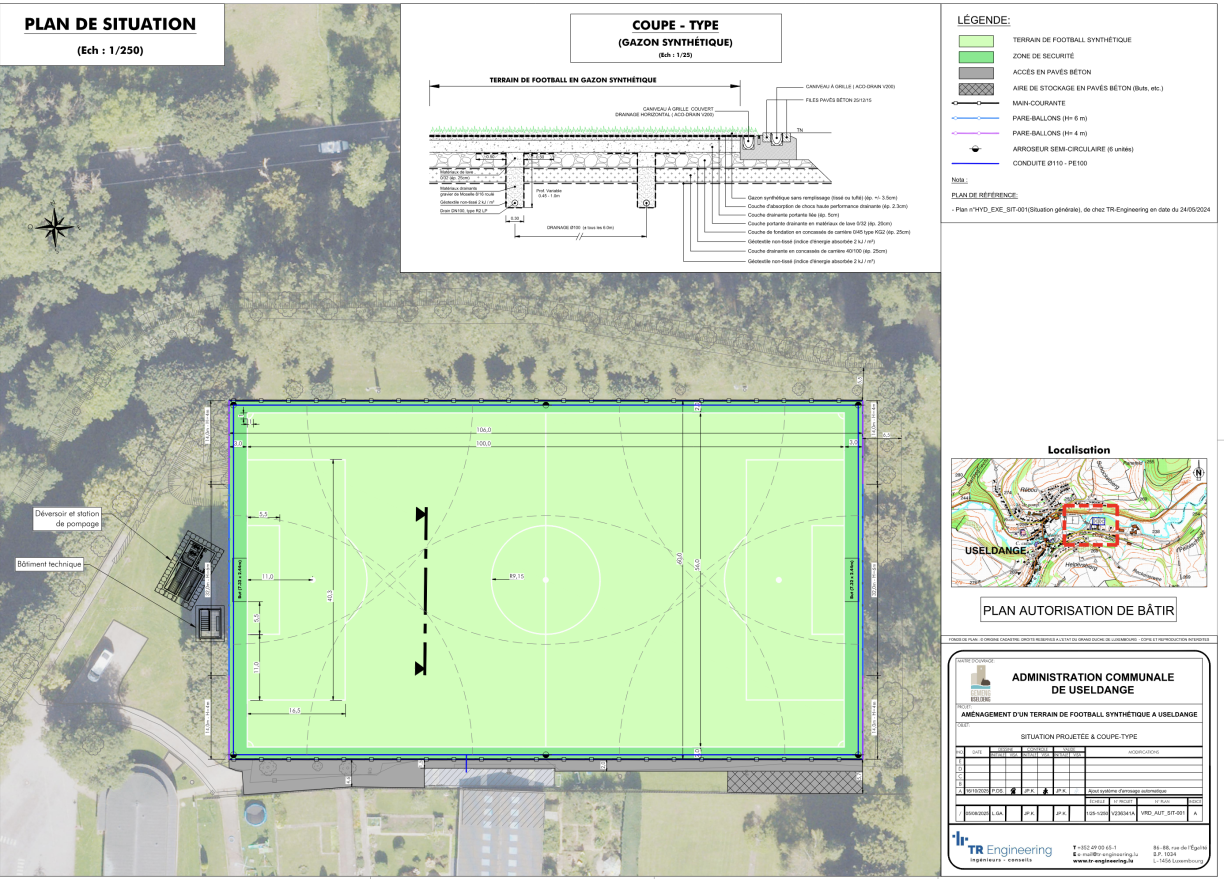

Depite this, young people in Useldange will be able to train on a new artificial pitch in the future. The municipality has obtained all necessary permits to build the facility 5m from the Attert, despite the high flood risk and the possibility that receding waters could carry microplastics from the turf into the river.

Anne-Marie Reckinger, AGE’s deputy director laments the gaps in the legislation but noted that existing regulations still allow authorities to protect water quality.

Researchers at the University of Osnabrück, in collaboration with the Federal Institute of Sports Science, concluded in 2023 that fibre loss and wear alone release 10–90kg of microplastics per year per football pitch into the environment. The University of Barcelona found that 15% of the longest plastic particles sampled at sea were fibres from artificial turf. Across the EU, up to 1,400 synthetic sports pitches are built each year.

The mayor must comply with the permit conditions and purchase the materials in the specified quality. Implementation ultimately depends on engineers and the know how of the company responsible for installing and maintaining the pitch in Useldange.

In Luxembourg, football is played on around 80 such pitches, according to the Luxembourg Football Federation (FLF), which says synthetic surfaces are popular because they are more resistant to bad weather and require less maintenance than natural grass.

However, natural football pitches also have an environmental impact due to fertilisation and other treatments. From 2031, a European ban will apply exclusively to pitches containing granules.