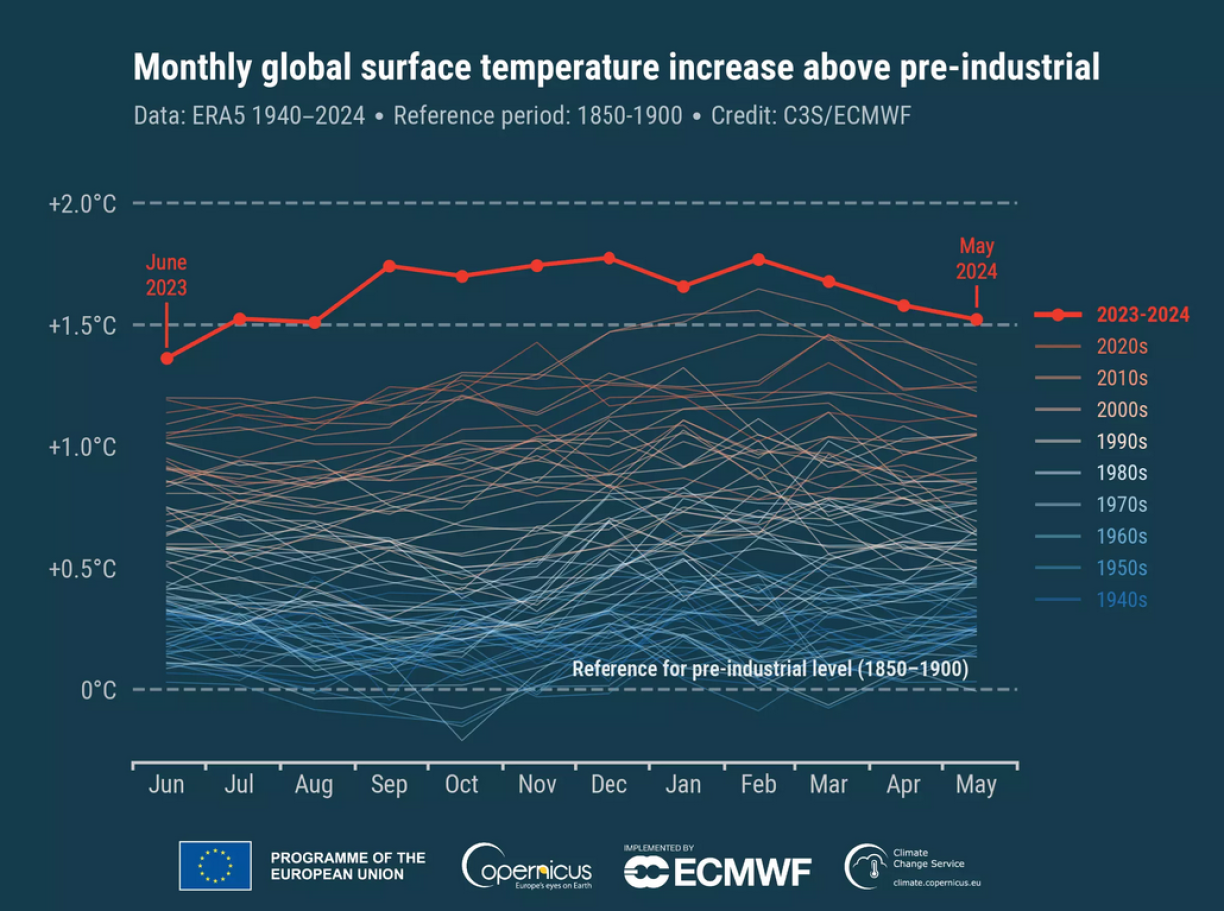

Did you know that each month from June 2023 to May 2024 has been the warmest globally since records began? (The data cited in this article cover the period up to mid-2024!)

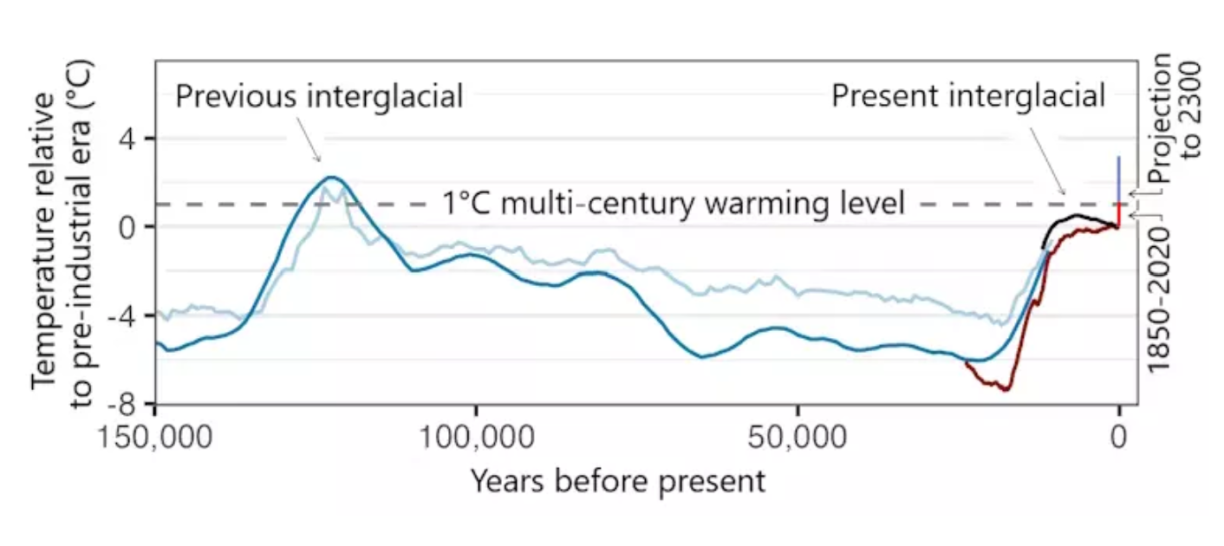

What’s more, according to the IPCC, this one-year period was the warmest in at least 125,000 years.

How can this be? It is not always warm in Luxembourg after all!

Yes, but here we’re talking about worldwide averages. When it comes to climate change, we need to remember two things:

That means, if one year is extremely hot or extremely cold, that is not direct evidence of climate change. But if, for example, the years 1961-1990 were significantly colder or warmer than the years 1991-2020, and a trend is observable over many years, then that is climate change.

In this episode of ‘Ziel mir keng!’, we will briefly touch on the global trends, before moving on to a more targeted analysis of a few physically measurable effects of climate change here in Luxembourg.

What do you think? Has it got warmer in Luxembourg since industrialisation? Is there more rain? Are there more droughts?

In this episode of Ziel mir keng!, we examined climate change in detail with the help of Andrew Ferrone from the Ministry of Environment, who is also Luxembourg’s representative on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

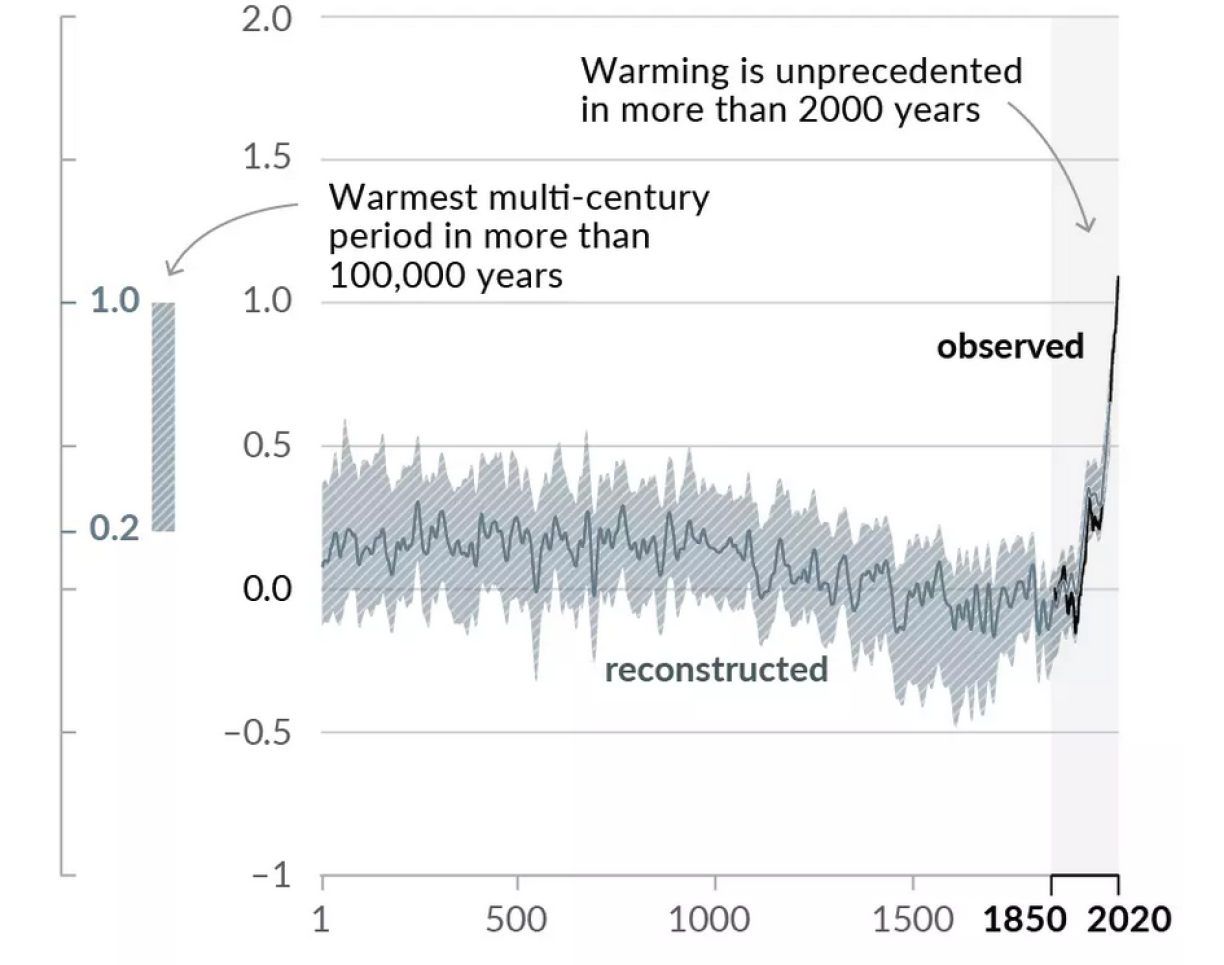

Let’s first look at global temperatures over the last 2,000 years. It can be observed that it has become rapidly and continuously warmer since industrialisation. That is unprecedented for this period.

And yes, there is a strong consensus in the scientific community that the current climate change is caused by humans.

According to a study, in over 99% of the publications on climate change that have been published in peer-reviewed journals since 2012, scientists agree that climate change is caused by humans.

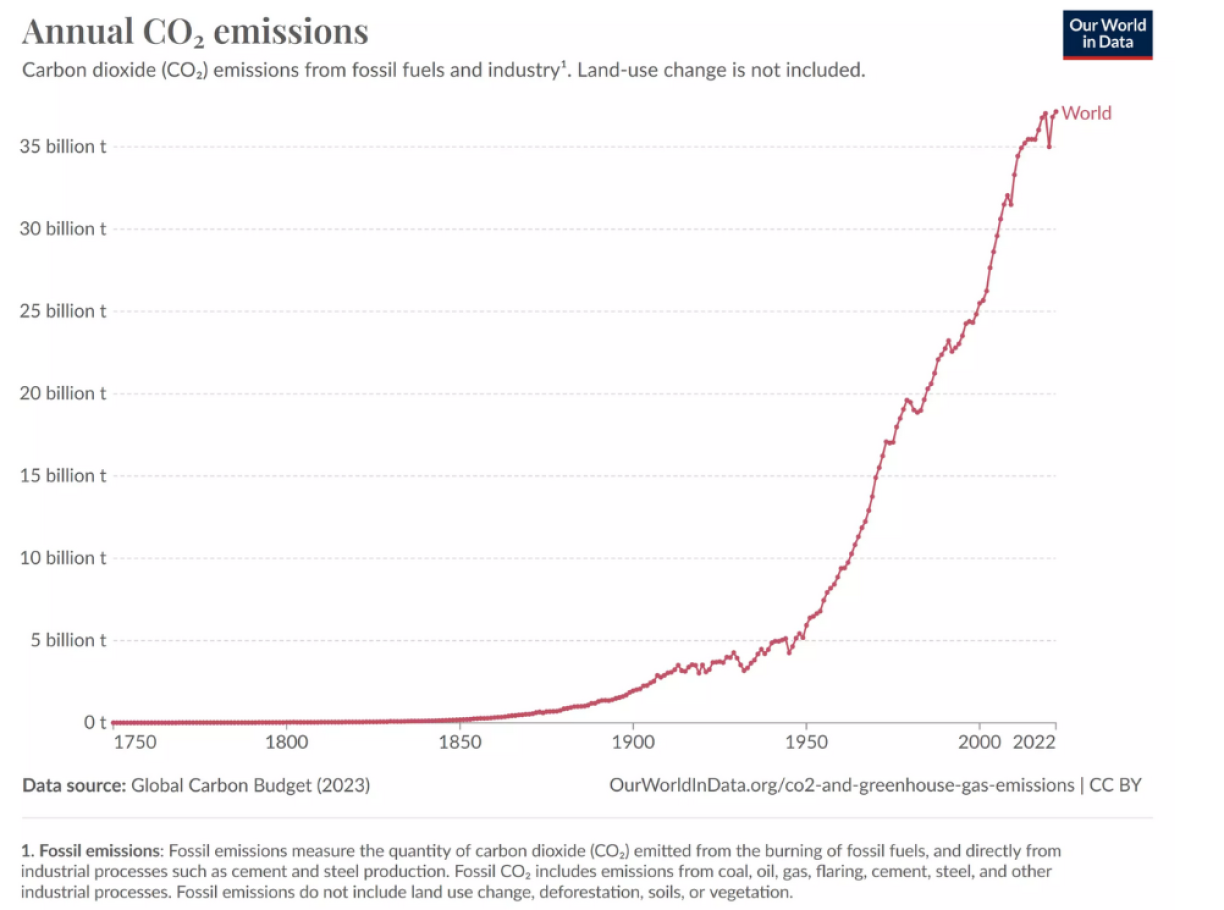

The physics behind how CO 2 and other greenhouse gases warm the climate has been understood for a long time and can now also be modelled with relative accuracy. And there’s no denying that we humans have released a lot of CO 2 into the atmosphere since industrialisation. The CO 2 content is currently higher than it has ever been in the last 2 million years.

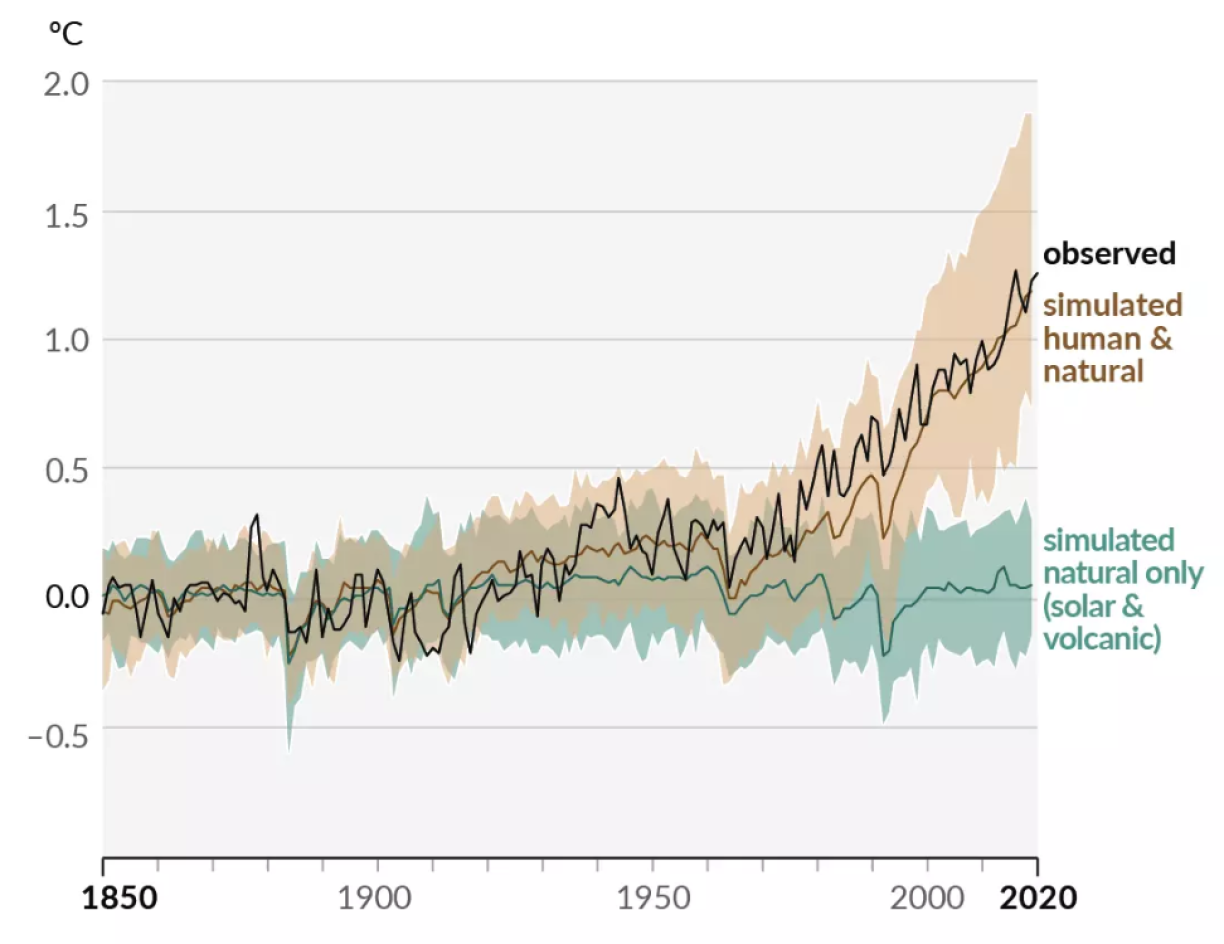

By the way, this is a model from the IPCC showing how climate change would have progressed without human influence.

Even though it is getting warmer worldwide, there are regional differences. In some regions, it gets warmer than average and in others less.

What’s more, temperature increases over the continents are higher than those over the oceans.

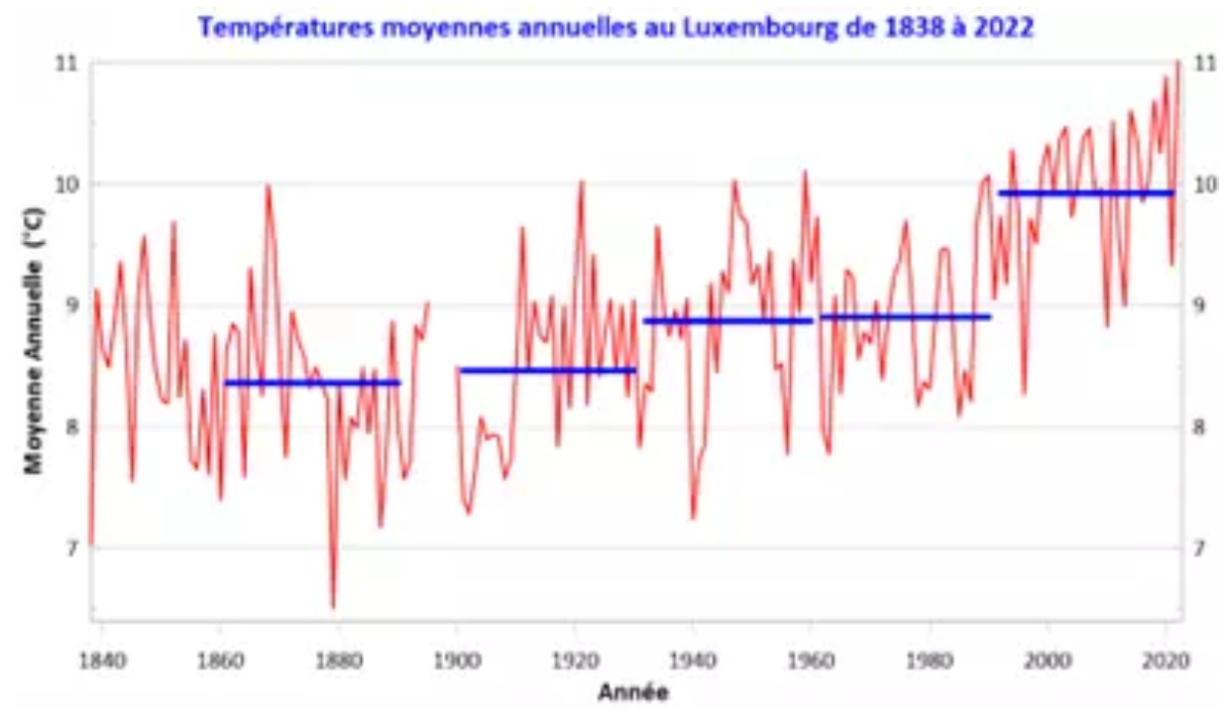

Let’s now take a look at temperatures in Luxembourg. Has it got warmer here?

Yes, it has. This graph shows that temperatures have increased continuously over the various 30-year cycles. In Luxembourg, the 1990-2020 cycle was 1.6 °C warmer than the 1860-1890 cycle.

In comparison, worldwide it has become 1.1 °C warmer in the same period. If we exclusively look at warming over the continents, the increase is 1.6 °C. Warming here in Luxembourg is thus almost identical to global warming over the continents.

Additionally, the ten warmest years in Luxembourg since records began all occurred between 2003 and 2023 (the data cited in this article cover the period up to mid-2024!).

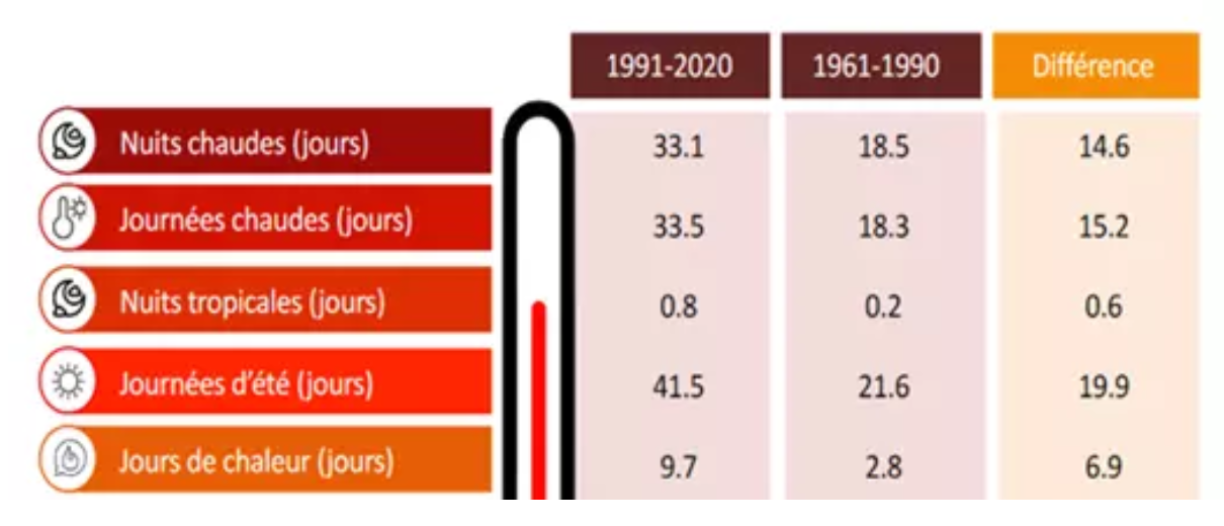

Let’s now compare the number of extremely hot days and nights.

Between 1991 and 2020, compared with the previous 30 years, the number of so-called heat days, i.e., days on which maximum temperatures exceeded 30 degrees, increased from 2.8 days per year to 9.7. So, more than three times as many.

The number of days that qualify as ‘summer days’, and nights that qualify as ‘warm’, has almost doubled.

Maybe it’s not such a bad thing if temperatures increase here in Luxembourg?

Well, unfortunately, there are also negative consequences.

What about, for example, the impact of warming on heavy rainfall in Luxembourg?

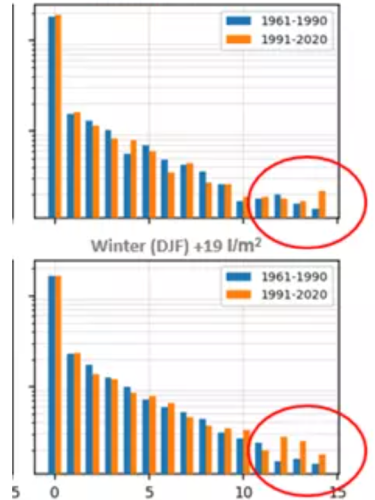

If we compare the same period, then the number of days with heavy rain has increased significantly in both winter and summer, by five days each.

Physics can help us understand why there is an increase in heavy rainfall when global temperatures rise. As the air gets warmer, it can store 7% more water in the form of water vapour with each degree. This was proved as early as the 19th century by physicists Emile Clapeyron and Rudolf Clausius.

Furthermore, more water also evaporates from the oceans when it is warmer.

So climate change increases the likelihood of heavy rain events – and also the risk of flooding, unfortunately.

Again, there have been floods in the past. And yes, floods are partly due to surface sealing – but also to heavy rain events. Not every single flood can be attributed to climate change. But the probabilities are increasing, and such events are becoming more frequent.

But what about droughts?

Interestingly, when we compare the same time periods, the number of droughts in Luxembourg also increased.

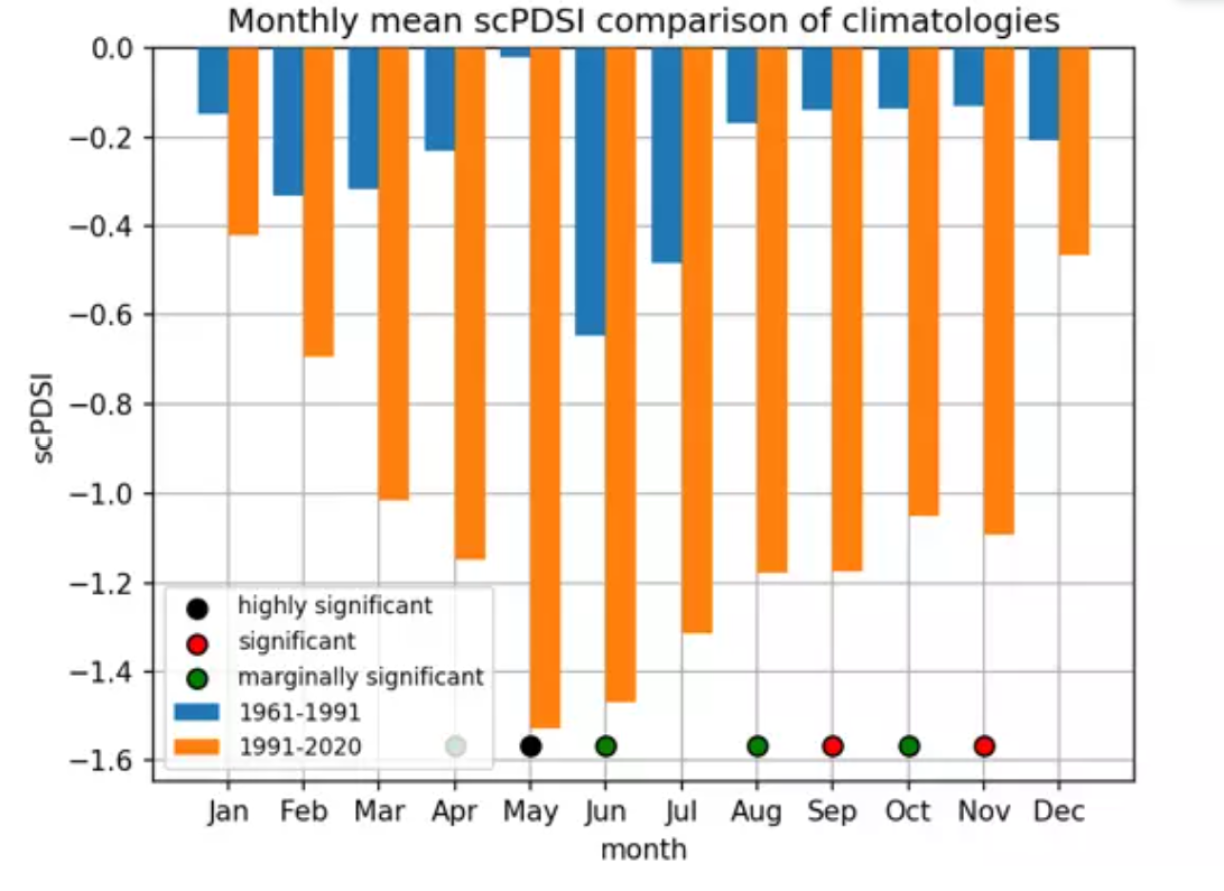

Measuring drought is more complex than heavy rainfall, because different factors need to be considered, such as precipitation over a longer period, soil moisture, sunshine duration, and so on. To do this, researchers work with a drought index.

The higher the value of that index, the more droughts will occur. Between 1961 and 1990, droughts occurred almost exclusively in June and July. In the 30 years following, this had already expanded to every month except January and December, where the risk remains very low.

Our farmers, horticulturalists, and gardeners can tell you a thing or two about it.

The drought index is an index of probability. It determines the likelihood, or in other words, the frequency, of droughts occurring. These probabilities were never zero, but they are now significantly increasing.

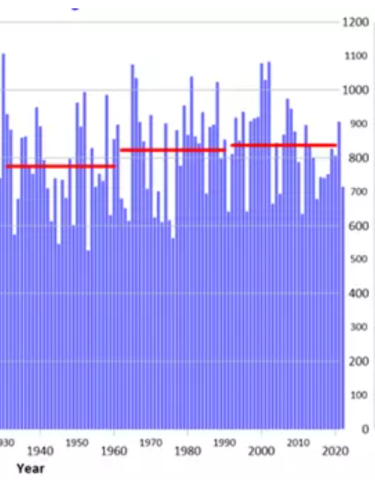

But now what about the overall rainfall amounts here in Luxembourg?

Well, the average precipitation quantities have remained relatively consistent over the years.

But it is evident that the seasons are changing.

Winters have become significantly wetter, with an increase of 19 litres of rainfall per square metre, when comparing 1960-1990 with 1990-2020. Meanwhile, springs have become significantly drier, with a decrease of 26 litres per square metre.

In the case of summer and autumn, however, we do not see any significant differences.

And finally, let’s take a look at the number of days of snow.

Between 1961 and 1990, there was an average of 41.4 days per year with at least 1 centimetre of snow in Luxembourg. In the 30 years afterwards, this number dropped to only 25 days (source: Meteolux). We thus have significantly fewer days of snow nowadays.

In this episode, we have only talked about the measurable physical effects of climate change in Luxembourg. But climate change naturally also has an impact on agriculture, biodiversity, our well-being, and social cohesion. But that’s for another episode!

Ziel mir keng! is broadcast on Sunday evenings after the programme Wëssensmagazin Pisa on RTL Tëlee and is a collaboration between RTL and the Luxembourg National Research Fund. You can also watch the episodes on RTL Play.

Author: Jean-Paul Bertemes (FNR)

Editing: Michèle Weber (FNR)

Presentation: Jean-Paul Bertemes, Michèle Weber (FNR)

Peer review and advice: Andrew Ferrone (Ministry of the Environment; at the time the article was being prepared: ASTA)

Data and graphics: ASTA/Andrew Ferrone; Meteolux/Luca Mathias

Translation: Nadia Taouil (www.t9n.lu)